|

|

Liberation, and

Flight

With the ransom

paid and the time and place of release negotiated, the ordeal was nearing

an end. As dawn broke after a final hard

night march through the wilderness on the morning of February 23, 1902,

Miss Stone and Katerina Tsilka found

themselves on the outskirts of a village not far from the town of Strumitsa. After attending to baby Elencha, the two women gloried in

a long bath, and began the process of recuperating their strength and

well-being.

Both women were

subjected to close questioning and interrogation, but as Turkish subjects,

the Tsilkas were naturally under greater threat of reprisal by Ottoman

authorities. Both Tsilkas prepared depositions with their

recollection of events, and Katerina's transmittal of a copy for the

American embassy revealed some of her frustration:

Salonique, Turkey, March 29, 1902

Dear Sir,

Your letter of

March 21st, is at hand. In the enclosed statement I have tried to

write all I can remember of our captivity which may assist in the

discovery of the villains, but in case I have failed to answer points you

may desire, I shall be glad to answer any questions you may choose to ask

me.

Mr. Leishman,

excuse, if I ask you a personal favor. Is there any possibility in

shortening our case with the government here? They keep us here

apparently without doing anything. Both my husband and myself have

been thoroughly examined, and now I do not see what they are waiting for.

My husband has been without work for the last seven months, and now we are

spending all the means we have. It is very hard on us.

Respectfully

yours,

Katerina Tsilka

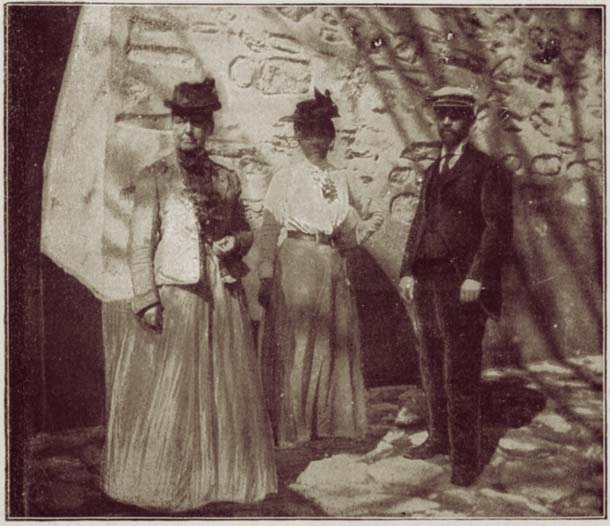

The Tsilkas and Miss Stone, 1902,

after the Ordeal

The following

month, James H. Ross, writing in Leslie's Weekly, of April 10, 1902, p.

348, summarized some of the difficulties the Tsilkas faced with the

Turkish authorities:

Strange Sequel of the Capture of Miss Stone

By James H. Ross

Immmediately preceding the release of Miss Stone by the Bulgarian

brigands who captured her, a cablegram announced that the husband of Mme.

Tsilka had been arrested charged with being a conspirator who had aided in

selling his wife into captivity. Since then, the public has heard but

little as to the sequel. The case is not ended. Neither is it settled.

Turkey never hurries. Neither Mr. Tsilka nor the friends of Miss Stone

know what Turkey will do. Technically Mr. Tsilka was not arrested, but was

detained and is under surveillance. When, on February 23d he knew by

telegraphic message from Serres to Salonica that the captives were

released, he planned to leave at once, to meet his wife. But the police

would not allow him to go. The Turks seemed to be very suspicious of him.

Such restraint as there was on their part was due to the fear that foreign

correspondents of the European and American press would make it hot for

them.

Mr. Tsilka. on February 25th, was finally allowed to leave Salonica.

Consular Agent Lazzaro conferred with the missionaries and with Vali Pasha

concerning his case. On Friday, February 27th, he boarded the train in

Salonica for Sofia and was called out before the train started and

detained. The police mudir said that he might go anywhere he pleased in

the Vilayet, but not out of the country. February 24th he was permitted to

leave Salonica by rail, to meet his wife and return with her. The Vali

showed Mr. Lazzaro an order from the Minister of the Interior telling him

not to let Mr. Tsilka go out of sight, and adding: "I think this is its

accordance with the wishes of the American legation." But he may have

misinterpreted the wishes of the legation. Mr. Tsilka repeatedly said:

"All I want is a fair trial without torture. If they can prove anything

against me, I am ready to suffer." It was possible that letters had been

forwarded to him from America, excoriating the Turks, and that they had

been intercepted. But he said, with truth, that he should not he held for

what another had written who was not under his control.

Assuming that he had been deceptive while living in Salonica with the

missionaries for six weeks they would have condemned him in severest

terms. Such baseness as was charged against him. viz.: Selling his wife

and causing so much anguish to so many hearts, in many lands for six

months, would have deserved heavy judgment in speech and judicial

punishment. But if he has been an innocent sufferer, like the missionaries

themselves and the kindred and friends of Miss Stone, any addition to his

sufferings by false charges and imprisonment is intolerable. If charges

against him are pressed, the civilized world will wait with wonder for the proofs.

If sound proofs are not forthcoming, his arrest will be regarded its an

act of cruelty, and Turkey will lose that much in the world's estimation.

Moreover, Miss Stone wields the pen of a ready writer, and if she is

convinced of his innocence, she will he unsparing in her denunciations

through the press. Her character and courage are well known.

As Mr. Tsilka himself has no objections to testifying, no one else will

object to his being examined by the authorities. For that purpose arrest

and imprisonment are not necessary. American influence can he exerted to

aid in securing him judicial and fair treatment. The commander in Serres

has persistently hindered the work of liberation and broken his promises

not to chase the band who held the captives, thereby imperiling their

lives. He is known to be hostile to Mr. Tsilka. The American principle is

to believe a man innocent until proven guilty. If innocent, Mr. Tsilka is

suffering for being associated with an American citizen. The Americans in

Salonica will turn every stone to help him, until he is proved guilty.

Nothing yet heard would be regarded by a grand jury in this country as

warranting an indictment. What Turkey will continue to do, time alone can

tell. It may do nothing more: it might do much more. For ways that are

dark and tricks that are vain, Turkey is peculiar.

LESLIE'S WEEKLY has special facilities for keeping its readers informed

of the political agitation through which Bulgaria and Macedonia are now

passing, and of the quality of the leaders who are the agitators, and

there are reasons for believing that the ransom of Miss Stone, the

captured missionary, may only lead to new and more serious troubles. The

Bulgarians, among themselves, before they obtained their freedom from

Turkey, in 1878, were a comparatively pure people. Now licentiousness is

bold and often brings no disgrace. The use of intoxicating liquors, aside

front the twines of the country, is probably tenfold what it was in 1860,

and the use of wine has greatly increased. Infidelity, bold and

aggressive, was scarcely known in 1860. Now many teachers, probably the

larger part of the influential men and a very large proportion of the

students, are said to be boldly godless. During the past ten years,

students have been expelled from the missionary schools for unmentionable

vices. Infidelity, rank socialism, and all forms of godlessness have

greatly increased. It seems probable that some of the ransom money paid

for the release of Miss Stone and Mrs. Tsilka has been supplied to be

used in preparation for incursions from Samokov into Macedonia.

Macedonia ought to be free. The only doubt is whether the resort, to

arms should be made. But the leaders of the Macedonian committee are men

of no principle and their followers become like them. Plans for various

inroads into Macedonia are being made. An American resident in Samokov

writes as follows:

When Servia fell upon Bulgaria, I went to see five student volunteers

take their summer night departure about 11 p. m. I respected them and my

heart was with them. As yet I have seen no one engaged to this Macedonian

movement whom I have respected, and whatever shall he done it will be done

chiefly under the guidance of those who hate God, at least so far as those

in Bulgaria are in this movement. All Macedonia wants freedom and will do

what will seem to lead to freedom, yet I fear that all the efforts will

result in much needless bloodshed, and I also fear that, in the end, no

real benefit will be gained.

There is apprehension among the American missionaries in Bulgaria lest

Miss Stone may not be the only captive by brigands. Fears are expressed

that other plotters may plan again to show that "little Bulgaria could

outwit great America and make her pay another ransom." One missionary has

been accustomed to travel alone on horseback, not infrequently from five

to twenty miles over old roads and mountain paths and often without any

path and through tangled bushes, striking for known landmarks miles away.

Twice, by anonymous letters, he has been threatened with death if he did

not pay money. He has disregarded the threats, and acted essentially as

though he had not received the letters. On the range of mountains among

which the Turkish troops chased the brigands who had Miss Stone, there is

scarcely any habitation. Hence the brigands are comparatively safe in such

a region with their captives. Some of the missionaries have notified their

associates and the official boards in this country, that if they are

captured they do not wish any ransom to be paid. They deem it wise that no

premium should he put on capturing missionaries.

On the 4th of March, thirty persons were brought to Monastir,

Macedonia, 100 miles northwest of Salonica, and put in prison. Their friends are not allowed

to see them. Arrests of suspected persons are made continually. The

prisons are full. The state of the country is very bad and there is great suffering, and many of the

sufferers are innocent. All the teachers at Racine, four hours' distant

from Monastir, have been brought to jail in Monastir. There is great need

that the European Powers should take up the matter of reforms in

Macedonia. An autonomy would solve many problems. Macedonia is honeycombed

with Bulgarian "committee" work. It was a political mistake to make

captives of Miss Stone and Mrs. Tsilka. Much sympathy for the Bulgarian

has been lost thereby. All Bulgarians do not approve of that step, however

much they may desire liberty in Macedonia.

Exchanges of

correspondence between Albania and the United States continued through

1902, and several letters found their way into print.

A letter from

Mrs. Tsilka, dated Kortcha, Albania, May 21, reports her again busily

engaged in her missionary work, which is in a prosperous condition.

The school at Korcha, which is in its boarding school department, had five

girls last year, now has eight. With abounding gratitude to God and

to the friends who have aided her rescue from the brigands, she and her

husband are devoting themselves with new energy to the work of

evangelizing their people. It may be also said of Miss Stone, that

though her labors are in another line, she is accomplishing much for

missions, for through her numerous addresses she is reaching a multitude

heretofore but partially, if at all, interested in missionary work, and it

is leading them to new conceptions of what this work is, and of the

character and abilities of those who are engaged in it.

[Missionary Herald, July 1902,

p. 272].

The following extracts

from a private letter from Mrs. Tsilka...give some details not mentioned

in the magazine articles: "Yes, we two women, Miss Stone and myself,

and the wee little woman who joined us later, went through fearful

suffering while in bondage. I have wondered at the capacity of the

human being for enduring misery...

"As for nursing, I lost

no chance, even among the brigands. The chief brigand fell one night

and injured his ankle, so that he had to be carried. When I offered

to give him all the help I could I never saw a brigand look so embarrassed

and remorseful as did he. While I was douching the sprained ankle

with hot and cold water, and especially when massageing it, he never

looked once at me. In a week, with this treatment, he was able to

walk a whole night with comfort. Though he never said 'thank you' to

me (for that is not a brigand's way), I knew he was grateful, for he saved

the life of my baby and me on more than one occasion...

Many of the brigands

brought to me their wounded and pus fingers to treat and cure. I am

sure that if they had been obliged to kill me they would have found it

very hard work to do so, for they 'had learned to love me,' as a young

fellow expressed himself. He was one for whom I treated four pus

fingers..."

[American Journal of Nursing, vol. 3, no. 3 (Dec 1902), p. 236-237]

Another Word from Mrs.

Tsilka

Mrs. Tsilka writes to

Miss Maxwell, from Kortcha:

"My adventures with the

brigands were so very dreadful -- very fearful; but, thank God! that is

all past, and to-day I am sitting down in a very bright cheerful room,

with my husband playing with Ellenchin, and I comfortably writing this.

You know. sometimes it seems so hard for anybody to live in this country

that many times we have been about ready to run to America. This

autumn some money was sent us from America to build a dormitory for the

girls. The necessary permit for the building was obtained.

Afterwards, when about half through, the government stopped us. All

the material was left exposed to the weather. It was done just to

give us trouble, for the government does not want improvements.

Besides that, the Greek Catholic Bishop persecuted us; they do not wish to

see Protestantism triumph. Besides these troubles, brigands are all

around us, and I can't help shiver at any gunshot in the night. If

we ever come to America, it won't be until next summer. I am afraid

to expose my darling any more dangers."

[American Journal of Nursing, vol. 3,

no. 5 (Feb 1903), p. 399

]

next section

|