|

Gregory and Katerina were back in Albania by the end of Summer, 1900.

Writing from Samokov to Boston, James W. Baird noted “On account of a law

suit, Mr. Cilka cannot leave Monastir vilayet and so has given up his hope

of going to Radovish & will work in Monastir field, most probably at

Kortcha.” Baird concluded his note with an interesting observation:

“There are reports of a rather larger number of deeds of violence than

usual, but the efforts of the Bulg. Revolutionary committee may be

responsible for much of that. That Committee has brought & will

bring only trouble & useless suffering on Macedonia. Perhaps its

vain efforts will cause Macedonians to think of a salvation unmixed with

political aspirations.”

On August 12, 1900, as she and Gregory waited at Monastir, Katerina wrote

to her old mentor in America, Miss Anna Maxwell:

Do not worry about us. We are perfectly happy—both because of God’s love

to us and of our devotion to each other. We have been on a missionary

tour these last two weeks. The American students were with us too. There

were no Christians in that place, so we hired two big rooms and did our

own cooking. The principal of the American school and Mr. Tsilka did the

dishwashing. Afterwards we had a man and girl to do our work, so we

devoted our time to Christian work. On the Sundays I thought Mr. Tsilka

would preach himself to death. The place was so crowded that the people

had to look over each others’ heads. I have done a good deal of medical

and surgical work here. The people are so ignorant of the laws of

health! A woman will come to me with a baby in her arms. ‘Sick,’ she

says, ‘has fever.’ A few questions, and I ask, ‘Do you bathe the baby

every day?’ ‘Oh no! no!’ she screams, expecting my approval of her not

bathing the baby. My prescription is usually castor-oil, regular feeding,

and a bath every day, and in a week’s time the creature is just as bright

and happy as any baby in America.[11]

Rev. Lewis Bond, writing to Boston on August 13, 1900 declared: “We are

very glad to know that there is a possibility of our mission being

reinforced with two new families if not with three. If but two come, I

fear the Albanians will have to wait. Mr. Tsilka will probably get clear

of his difficulty with his would-be brother-in-law very soon now. I hope

the way will be open for him to enter the Albanian work a year hence. Our

friends in Monastir & Prilep like him very much. And his wife is

excellent.”[12]

On October 2, 1900, Bond wrote again to Barton and reported: “Mr. & Mrs.

Tsilka have entered upon their Albanian work. They will reside for the

present – perhaps permanently – at Kortcha…Mr. & Mrs. Tsilka have made an

excellent impression here and at Prilep and we anticipate much good from

their efforts in Albania. Mrs. Tsilka is handicapped at the start by

ignorance of the language, but she is giving herself heartily to the

work. I sincerely hope you will not fail to appreciate the

£30

which in put in our estimates for past support of Mr. Tsilka. The

Seminary have pledged his salary for two years but Mr. Tsilka assures me

that no definite sum was named and that a number of those you promised aid

conditioned it on their success in securing good pastorates. Of course

nothing was given toward their traveling expenses from America…Native

agency at this station is in a somewhat hobbling condition.”[13]

Katerina’s

initial difficulties at Kortcha were reflected in a second surviving

letter she wrote to Anna Maxwell:[14]

Kortcha, Albania, Turkey,

Europe

January 21, 1901

My dear Miss

Maxwell,

Since we

arrived here it seems to me as though I have sunk way down into the deep

of the sea. Shut in from all communication with the civilized world, no

papers, no people of enlightenment. Mail comes only twice a week, and

that not to be depended upon, for the postmaster (a Turk) distributes it

whenever he pleases. The women are ignorant as goats, for they are not

allowed to go out of their houses. They think it terrible for women to be

in the presence of men. They must use neither eyes nor mouth. Obedience,

and only obedience, is their virtue. All my actions seem wonderful to

them. The men treat me very respectfully, even the Turks. Woman is not

respected because she is ignorant, and does not know how to respect

herself. I have more nursing and doctoring than I can possibly do. There

are few doctors, whose diplomas say ‘Good only for the East.’ That is,

they go to a medical school in Athens and study a few things, and then get

a diploma with the above statement. You would have smiled if I told you

that I was called to a consultation by the doctors here on a case of

septicaemia. I do miss nursing under a competent doctor. They are trying

to get permission from the Sultan to build a hospital. I do hope that he

may grant it, for it will give me a fine chance for training girls how to

nurse the sick. There are very interesting cases of sickness. To-day I

visited one of the Bey’s (or Lord’s) houses. Everything about the house

was royal, but the women – oh, so blank! They showed me some of their

fancywork, and their skill and taste is wonderful. There was a chemise

embroidered most wonderfully with gold, and its value is over eighty

dollars. I do wish you could visit here sometime. Our line of work is of

every kind. My husband teaches a few hours a week in the girls’

boarding-school. This school was daily, and this year we decided to make

it boarding, and then only we can have the girls at our command, and mould

their character and training in the right direction. I plan to start a

class in nursing in the school. Besides all these things, I have a house

of my own to look after. My health has been perfect. Since I came here I

do not know that I have a stomach. The climate is even better than at

Asheville, N.C. The only calamity is poverty, and that is because of the

terrible rule of the Turks. There are rich mines, but they will not

permit their opening. There is so much of which I want to write, but,

knowing how busy you are, I shall have to control myself. Let me say that

my going to America would have been useless had I not taken the nurse’s

training – it is of such a help to the people here.

That I am

homesick for America I cannot deny, but then I feel strongly that my duty

calls me here. I am enjoying my home life, and we are very congenial in

our work. Mr. Tsilka is so interested in my work that he plans to take a

medical course in America when we come to visit. I have wished to write

you long before this, but, as I have said, my time has been simply

crowded. Please kindly remember me to Miss L. Welch (I do not forget

her), Miss Stone, and Miss McArthur. I do not dare to expect a letter

from you, but if I do get one I shall be more than happy.

Very respectfully yours,

Kathrina Stephanova Tsilka

A third letter

from Katerina to Miss Maxwell on May 16, 1901 showed that the Tsilkas’

work continued to be as arduous as ever:

We have had

hard work this year, and it won’t be any easier next year. No Christians

at all, and training the girls is a terrible job, but, as I have expressed

myself while yet in America, I did expect hard work. You know one wishes

to accomplish so much in a short time. I want to have the boarding-school

well organized and then start my training of nurses, but it will take some

time yet. We have no hospitals. This year I have felt so strongly the

need of nurses. The world needs more the nurse than the doctor, because

the nurse, in many cases, can do the work of a doctor as well as of a

nurse. There are a few doctors here, but they are comparatively useless.

Their diplomas say ‘Good only for the Orient’ – that is, their work is not

wanted elsewhere. I have had the whole town and surrounding villages come

to me for help. Of course, I cannot help all, for I am not a doctor, but

I can do good in many cases. I have opened an abscess in the breast and

was very successful, so much so that the doctor here reported me to the

government, but the government, instead of stopping me, asked me to be a

government nurse—that is, to be paid by the government and sent to visit

any case they may ask me. But, of course, I told them that my object is

not money, but to help the needy. They admired my diploma. It is a very

great thing to have a trained nurse in a place like this. There are some

very interesting diseases here. There is one which begins with chill and

fever, then eruptions at all the joints. If the patient does not eat fish

and chicken he recovers, otherwise goes into consumption. This place is

very healthy, but the people do not know how to guard against contagious

diseases.[15]

Speaking of the

Tsilka's activities in Albania, upon their return to Europe, the New York

Daily Tribune of February 19, 1902 (page 9) described them this way:

Mrs. Katherina Stephanove Tsilka...is a native of Albania[!]. During

several years which she spent in this country, Mrs. Tsilka took a partial

medical course, studied for two years at the Moody Bible School,

Northfield, and was graduated as a trained nurse from the Presbyterian

Hospital Training School. Just before sailing for her home country last

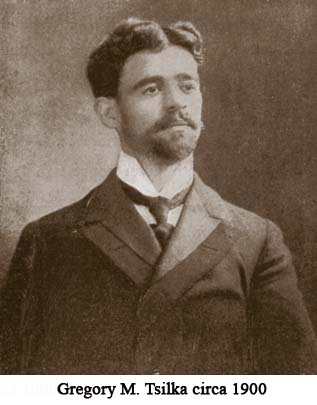

year she was married to Gregory M. Tsilka, one of her own countrymen who

had been her classmate in the American Mission School at Salonica [Samokov],

Turkey and with whom she had disputed academic honors. Since returning to

her country the couple have been located at Kortcha, Albania, in Turkey,

where, independent of any board, they have been engaged in active

missionary work among their people.

Mr. Tsilka was graduated in 1900 from the Union Theological Seminary of

this city, and his classmates, headed by the Rev. Howard A. M. Briggs,

president of his class of '00, have endeavored to make themselves

responsible for the financial support of their work. At present the

interest is centered on the support of five Albanian girls in the school

for girls established at Kortcha by Mr. and Mrs. Tsilka. This institution

has forty students, all that the resources permit. It is the only

Christian school for girls in Albania. Mrs. Tsilka's efforts have been

devoted, since her return, to benefiting her countrywomen physically as

well as spiritually. It is her aim to establish a work among the women

which shall lead them so as to understand the general laws of health that

better sanitary conditions may prevail in their home and that the children

may have better hygienic surroundings.

In a letter to a friend in this city not long ago, Mrs. Tsilka gave

some insight into her work. She said:

We began in the girls school with three pupils, and have increased

the number as money would allow. We feel that little can be done unless

the girls are taken from the bad influences of their homes and put under

Christian influences and everyday example. If you know any man or woman

who would like to give a helping hand to a noble cause, let him or her

support a girl in the school. The expense for each, including board,

tuition and room, is $40 a year. Mr. Tsilka is working with and preaching

to the people. I am, meanwhile, trying to win their confidence and

affection by relieving physical suffering. We are having a hard time, but

we know we are needed here and we shall stay and work, and trust God for

the rest. The country is beautiful. It is only the people who are not in

tune with God. As I go to my patients, Mr. Tsilka accompanies me, as it is

not safe for a woman to go alone. The people are so interested in my work

of nursing and healing that they occupy nearly all of my time and are

beginning to come to me. Our girls in the school are nearly naked. Their

clothes are so patched that it is almost impossible to see the original

fabric. How often I have thought of the many cast off clothes in America.

It was not

obvious from the letters (or the surviving extracts) written to Miss

Maxwell, but Katarina was pregnant and sometime in the latter part of the

summer of 1901, she gave birth to her firstborn, a baby boy named Victor.

As described in a later letter, Victor was baptized by the Tsilka’s

colleague, Rev. Lewis Bond, probably in Monastir, where the Bond family

was stationed. Because she needed to recuperate, had not seen her

parents, and Victor was their first grandchild, the Tsilkas decided to

travel to Bansko for a short visit. The episode that would forever change

the lives of the Tsilkas has already been mentioned, but two letters

succinctly introduce what transpired on an early September afternoon in

1901:[16]

Salonica, Turkey

October 7, 1901

Dear Miss

Ryder:

You will wonder

why I am writing to you instead of Katharine, but what follows

explains:

On our way from

Mrs. Tsilka's home to our work we were surrounded by a large group of armed

men -- about twenty-five in number--and carried into the forest. After

that they took Miss Stone and my wife. They kept the rest of us all night,

and in the morning they were gone, having carried with them Miss Stone and

Katharine.

It was pretty

nearly one month before we got any answer from them, and now they ask one

hundred thousand dollars ransom for both of them. They must be saved soon.

Miss Ryder, the friend of my wife, is my friend too, so I confess that she

is in the family way of six (?) months. Victor, dear little Victor

died. So please do something and collect as much as you can from the

nurses and some of the friends, and send it by mail to Salonica,

care of Dr. House. There is mail connection with Salonica for

money-orders. Enclosed you will find a letter for Miss Bell Judd--I have

forgotten her address. Please forward it.

Please tell the

story to the following persons: Mrs. Anna Cross, 6 Washington Square, New

York City; Mrs. Walton, Munn Avenue, East Orange, N.J., Mr. Kennedy,

Presbyterian Hospital, New York City; Mr. Russell

Sturgis, Mrs. Kirkner, Plainfield, N.J.

These are some

of my wife's friends, whom she wants to know about it, and help if they

can with something. Miss Ryder, please pray for the safety of your friend

and my wife.

Hoping this

will find you well, I am

Respectfully yours,

Gregory M. Tsilka

Miss Ryder

received a second letter from the Tsilka's colleague, Rev. Lewis Bond in October 1901:[17]

Vodena, Europe,

Turkey

Miss Lucy F.

Ryder, New York

Dear Miss

Ryder:

Your letter of

September 26 reached me as I was about starting for this place. I wish I

could tell you of the release of our dear friend, Mrs. Tsilka, and Miss

Stone. However, as to that you would have the announcement in the New York

papers quite as soon as we should know it here. Perhaps I may give some

items about the capture which have not appeared in print. Mr. and Mrs.

Tsilka, Miss Stone, four or five young native lady teachers, our

Bible-reader--female,-- and several boy students were captured September 3

on the road from Bansko to Djumaya. A little in advance of this party of

Protestants was a man on horseback, presumably bound for Djumaya. This man

was severely wounded, and our friends were halted by a party of brigands

numbering from thirty to fifty, according to the varying estimates. One of

the girls says that about fifteen rifles were pointed at them. All were

obliged to dismount and go into the woods two or three miles off the road.

The wounded man, who seemed to be a Turk, walked with great difficulty,

and when they came to a halt he was put out of his misery. The robbers

asked for money, watches and other valuables, but did not search pockets

or use any roughness with the ladies. Mr. Tsilka, supposing he would be

taken captive, managed to pass on to his wife some money, about

twenty-five dollars, which he had. First of all Miss Stone, who had been

holding a summer-training school with Mrs. Tsilka's assistance, was taken

off by herself. Presently Mrs. Tsilka was taken in the same direction. The

horse of the Turk and two muleteer horses were taken. One of the brigands

came and, looking over a lot of things scattered on the ground, picked out

Miss Stone's Bible and, putting it under his arm, walked back. It is

supposed that our two sisters were taken during the night to a place of

safety. Mr. Tsilka and the others were kept at the halting-place, silence

being enjoined. At daylight they found that their guards had disappeared

and they returned in sadness to Bansko. The brigands spoke Turkish only,

and were very sparing of speech. Some had their faces blackened or wore

masks. Some wore Turkish uniform, other Albanian clothing, and a few were

attired as shepherds. It is my opinion that they were all Bulgarians. Mr.

Tsilka was at Salonica last week and wrote me that he had received three

letters from his wife, written, I suppose, at the dictation of the captors

to further the getting of the ransom--twenty-five thousand dollars. As to

anything further, the papers have published all and more than we know. We

are simply praying and waiting. It has been a sad season for Mr. and Mrs.

Tsilka. Their beautiful baby boy, Victor, whom I baptized before they

started for Bansko, died at the home of Mrs. Tsilka in Bansko. Then Mrs.

Tsilka was dangerously ill and started to come to our annual meeting (In

the New York Observer of September 19 I have written a short quarantine

experience which may interest you.) But we rejoice that our suffering

friends are all persons of strong Christian character. No real evil can

come to one who is in close touch with Jesus. We pity the brigands and

sympathize with the captives. Mrs. Bond is here with me touring. I will

pass on to Mr. Tsilka your kind word of sympathy.

Footnotes for this section

[9]

Ltr, Rev. Lewis Bond, Monastir to Rev. James L. Barton, Boston, dtd

29 Mar 1900, American Board of Commissioners for Foreign

Missions (ABCFM) Papers, Microfilm Reel 578, Frames 0279-0280.

[10]

Ltr, Rev. Lewis Bond, Monastir to Rev. James L. Barton, Boston, dtd 6

Jul 1900, ABCFM Papers, Microfilm Reel 578, Frames 0282-0283.

[11]

Ltr, Katerina Tsilka to Miss Anna Maxwell, dtd 12 Aug 1900, extracted

in “Foreign Department” column, American Journal of Nursing, vol. 2,

#6 (March 1902), p. 473.

[12]

Ltr, Rev. Lewis Bond, Resen, Eur. Turkey to Rev. James L. Barton,

Boston, dtd 13 Aug 1900, ABCFM Papers, Microfilm Reel 578, Frames

0283-0284.

[13]

Ltr, Rev. Lewis Bond, Monastir to Rev. James L. Barton, Boston, dtd 2

Oct 1900, ABCFM Papers, Microfilm Reel 578, Frames 0284-0285.

[14]

Ltr,

Katerina Tsilka to Miss Anna Maxwell, dtd 21 Jan 1901, included in the

“Foreign Department” column, American Journal of Nursing, vol. 2, #6

(March 1902), p. 473-474.

[15]

Ltr,

Katerina Tsilka to Miss Anna Maxwell, dtd 16 May 1901, extracted in

the “Foreign Department” column, American Journal of Nursing, vol. 2,

#6 (March 1902), p. 474-475.

[16]

Ltr,

Gregory M. Tsilka to Miss Lucy Ryder, dtd 7 Oct 1901, included in the

“Foreign Department” column, American Journal of Nursing, vol. 2, #6

(March 1902), p. 475.

[17]

Ltr, Rev.

Lewis Bond to Miss Lucy Ryder, dtd Oct 1901, included in the “Foreign

Department” column, American Journal of Nursing, vol. 2, #6 (March

1902), pp. 475-476.

|