| |||

|

Katerina Dimitrova Stephanova |

|

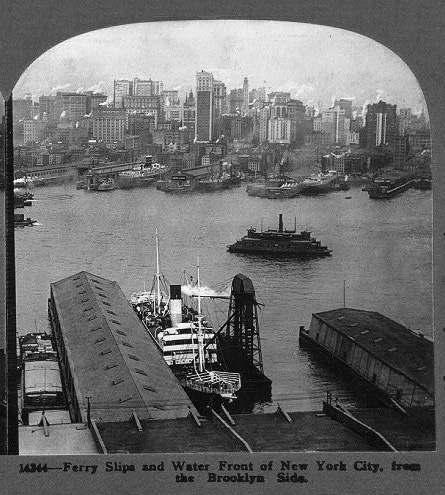

Katarina’s personal memoir does not report the exact date, or the name of the ship she boarded, which brought her to America. However, the 1900 census states she arrived in America in 1892 and given the limited number of people who traveled from Bansko to America in that year, checking through Ellis Island passenger lists, there’s little doubt that she is the 23 year old female passenger “Ka. Stefanov” from Bansko, who embarked on the steam ship Pennland at Antwerp, Belgium, and arrived in New York on Monday, August 15, 1892.[†]

Having mastered English as a student in Samokov, Katerina would have had

an easier time of getting her bearings in New York than many immigrants

from Eastern Europe. Had she spent three cents for

that day’s New York

Times, she would have read through a barrage of news about politics,

strikes, and one story that still resonates today – news that Lizzie

Borden of Fall River, Massachusetts was considered by many to be

innocent of the crime that we have come to recall through these familiar

couplets: But Katerina likely paid no heed to the news that day. The sights and sounds of New York were all-consuming. And the East Coast weather that greeted Katerina as she passed through Ellis Island was fine – Hudnut’s Pharmacy on Broadway recorded an average temperature of 71 7/8 degrees on Sunday, and the beginning of the work week was forecast to be just as agreeable. Katerina’s arrival in mid-August 1892 was especially propitious, for she landed just days ahead of a cholera outbreak which had traveled across Europe to Hamburg and affected passengers bound for America. When the ship Moravia sailed from Hamburg on August 17, all was well, but when it arrived in New York harbor on August 30th, twenty-two passengers had already died enroute. A speedily composed presidential proclamation by Benjamin Harrison imposed a twenty-day quarantine on all ships coming from infected European ports.[6] Several later-arriving immigrant ships belonging to the Hamburg-Amerikan Line showed an even higher number of passenger fatalities. The weeks and months following were especially difficult for immigrants from Eastern Europe who were under suspicion of carrying life-threatening disease. Katerina makes no mention of the situation, but a casual perusal of newspapers and magazines published during the autumn of 1892 reveal a growing fear of, and hostility to the newcomers.

But to return to Katerina’s memoir: After my graduation from the American school in Samokov, I went back to Bansko and taught at the very same elementary school which I had left eight years before. During the three years I stayed there I realized that my education was insufficient to satisfy my ambitions and I began to think of going to the United States that I considered to be the source of education and culture. My aim was positively achieved, but not without trial and suffering. Through the intercession of a former teacher of mine, I was accepted to work temporarily in a private boarding school in New York. In the letters I exchanged with the principal of that school we had arranged to meet at a certain day and hour at the Central Station of New York. In order to be recognized I was to wear a white kerchief tied around my arm. I traveled with the money I had saved during my work as a teacher, which was just sufficient to bring me to New York. I was punctual for the appointment, white kerchief and all, but nobody came to meet me.[††] For more than an hour I waited there, embarrassed by the crowd, painfully conscious of the few dollars I had in my pocket. Finally I went to a cab, showed the cab driver the address of the boarding school and asked him whether he could take me to it for a dollar. So I was taken to the place, rang the bell, and when the so-called principal appeared I attempted to embrace and kiss her but she drew back and blushed as if annoyed. I swallowed my disappointment and tried to be pleasant but she remained cold and distant. The address she had given me was a kind of office. After the preliminary exchange of questions and answers she took me to her home and to what was to be my room. It was a pleasant room, nicely furnished, and very soon I forgot all the unpleasantness of the day and went to bed. The next morning I woke up early, put on a nice dress in which I thought I looked suitable for my future functions (I thought I was going to teach). But the stern old lady said it wouldn’t do and gave me to put on an old dress in which I looked positively ridiculous. Some girls look well in anything they put on, but this was not my case. Then she told me that for the moment I was to tend to the house, to clean, wash and cook. In brief, I realized that she had taken me not to teach, but to be an ordinary servant. The place was not a boarding school at all; she had three or four girls to whom she gave private lessons, that was all. For three months that lady treated me like a slave; she spoke to me harshly, fed me poorly, and besides the housework, she gave me to do piles of drawings, when she found I was rather good at it. Later I learned that she sold the drawings. One day, as I was going to a nearby shop, a pleasant-looking lady stopped me and asked me whether I wouldn’t like to go to her house right by the corner and have a nice chat together. “I have been watching your some time,” she said. “You are a stranger and you do not look well; you do not seem to have any friends, either. Would you like me to be your friend? Could I do anything to help you?” Her manner was so frank and open, her face so gentle that at once I felt I could confide in her unreservedly. She introduced herself as Miss Austin, asked what my name was, and asked me to tell her everything about myself. “We know the woman with whom you are staying,” she said. “She has had other victims like you. Some of them ran away, we do not know where, some we succeeded in rescuing. She always takes girls who come from abroad, who know nothing about this country, and have no friends and uses them as servants without paying them anything. Won’t you stay with us for a while until we find something more decent for you?” I told her that I had come to America to improve my education, but at the same time I had to find some kind of work for my living. She told me to go to them as soon as I could manage; that same day or the next. That evening I went back to the old lady, cleaned the house, prepared the table for supper, packed my trunk and waited for her to come home. When I told her that I was leaving, she got very angry, said that I was mean and ungrateful, that I had been left in her charge and she wouldn’t let me go. I only smiled. I felt triumphant, but also a little sorry for leaving her alone to her life without joy. But just the same, the following morning, I took my things and went to the Austins. In my new temporary home I was once again free and happy. They took me to church, to socials and entertainments and treated me as their own child. I was introduced to many people and made new friends who remained such for many years thereafter. I had regained my personal dignity and confidence in my future. In the meantime, Mrs. Austin had arranged for me to go on a scholarship basis to Northfield Seminary in the state of Massachusetts, a kind of junior college where I could get preliminary preparation for teaching, evangelical work, or to continue my education in an advanced school.

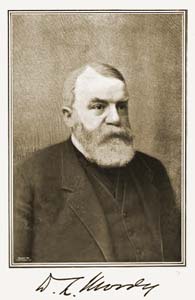

The three years I spent in Northfield were years of complete happiness. The founder of the school, Mr. Moody, and its principal, Mrs. Hull were exceptional people, loved by all the students of whom there were 500. I graduated in 1895 and for the next two years did various kinds of work, trying at the same time to decide what to do next and to arrange something for my further education.

A query to the Northfield Mount Hermon School in 1975 slightly contradicts Katarina’s recollection of her sojourn there (the school’s records show 1893 to 1896) and the following article appeared in the February 28, 1902 issue of the Springfield Republican qualifies that she did not actually graduate from the seminary:

Was Student at Northfield The people at Northfield have followed with close interest the reports of the captivity and the release of Miss Ellen M. Stone and Mme. Tsilka from the Bulgarian brigands, for Mme. Tsilka was formerly a student at the Moody seminary for young women. Mme. Tsilka (Miss. Katarina Stephanova) was born in Bansko, Macedonia, in 1870, of Bulgarian parents. She was educated in the Greek church, but was converted to Protestantism and joined the Congregational church at Samakov, Bulgaria (sic). Her mother was a member and her father an attendant of the Congregational church at Bansko. Her parents were farmers, the father selling lace from city to city. Miss Stephanova graduated from the mission school in Samakov, Bulgaria, through which she worked her way. She was six months in the United States before applying for admission to Northfield Seminary. During that time she was engaged in kindergarten work with Miss Coe in East Orange, N.J. Being fond of books and studies, she learned to read and speak the English language in a few months. She entered Northfield seminary in September 1893, at the age of 23, and remained until June, 1896, but did not graduate. From Northfield she went to the Presbyterian hospital in New York city, and became a trained nurse. Her object to coming to the United States was to educate herself for a missionary, to return and work among her people. While a student at Northfield she was engaged to a young Bulgarian, who died in his second year at Union theological seminary.[†††] It is understood that she met Mr. Tsilka when engaged as a nurse with a sick person in the Adirondacks, after leaving the Presbyterian hospital. He was a medical student at the time, or had possibly graduated from the medical college.[7] Footnotes for this section [†] Coincidentally, Lucasz Kaczmarek, the Ruthenian great great grandfather of the creator of this website, embarked on this same ship in Antwerp two and a half years later, arriving at Philadelphia on April 22, 1895. Thirty-one years later his granddaughter would become the wife of Katerina’s nephew, Dimiter Ivanov Stephanov. Their daughter is my mother. [‡‡] Katerina’s brothers, Constantine and Nikola were to follow their sister to Ellis Island. Constantine was "Kosta Stefano" a 20 year old native of "Bulgary" who arrived on the SS Westernland from Antwerp, on August 15, 1893. Nikola was "Nikola Stefanoff" a 19 year old native of "Banska" in "Bulgarian Turkey" who arrived on the SS Southwark from Antwerp on September 21, 1897. Presumably Katerina greeted her younger brothers at the pier! Her third brother, Alexander, arrived at Ellis Island on the ship Aurania, on September 10, 1903. [6] “Outbreak of Cholera and Quarantine at New York Harbor.” Harpers’ Weekly Magazine, 17 Sep 1892. [‡‡‡] It is virtually certain that Katerina was engaged to Lazarus Konstantine Kuchukoff (1868-1899) who died almost a year before she married Grigor Tsilka. The Obituary Record of Graduates of Amherst College for the Academical Year Ending June 27, 1900, 4th Printed Series, #8 (Amherst, Mass.: The College, 1900) pp. 282-283 includes this sketch: Class of 1897 LAZARUS KONSTANTINE KUCHUKOFF, the son of Konstantine and Maria G. (Kuchukoff) Obetzanoff, was born at Bansko Razlogg, an out-station of the American Board of Missions, Macedonia, Turkey, March 22, 1868. After the death of his father, who was a Bulgarian, he took the family name of his mother. About 1884 he was apprenticed to a tailor in Sophia, the capital of Bulgaria. Two or three years later he returned to Bansko, and began to attend the services of the Evangelical church, together with his mother. Both were converted, and united with the church, March 27, 1887. Soon after, through the influence of his pastor, he became a member of the American Collegiate Institute in Samokov, Bulgaria. The third year of his school life, he was drafted into the Bulgarian army, but being a Turkish subject, he deserted, and returned to Bansko in November, 1889. From that time until the summer of 1890 he worked at his trade as a tailor, and on Sundays preached to the small evangelical community at Banya, a village near Bansko. In 1890 he came to the United States, and was fitted for collage at the State Normal School in Fredonia, N.Y. From September, 1897, to September, 1898 he was a member of the Union Theological Seminary, and from Oct. 6 to the last of December, 1898, of the Junior class in Auburn Seminary. After about two months in the City Hospital, he went, on the advice of his physician, to the Adirondacks, but deriving no benefit from his stay there, through the kind offices of a seminary class-mate he was enabled to make the journey to New York City, in the hope of returning to his native land. He died of consumption, in St. Luke's Hospital in that city, May 30, 1899. He was a man who commanded the respect and love of those who knew him in college and seminary. [7] Springfield (Mass.) Republican, 28 Feb 1901, p. 7.

|

| cochranfamily.net |

Richard M. Cochran, Ph.D. |

rcochran@tucker-usa.com Copyright 2009 | All Rights Reserved |